When walking through the beautiful trails on the Western side of Mount Nerone, passing by Rio Vitoschio, Ca Rossara, Fosso del Mulino (Mill Ditch) and Mount Cardamagna, I have always been intrigued and fascinated by “The Carda”. Many times I wondered for instance if the origin of the name itself, spread and used in quite a large area around the Pian di Trebbio pass, came from the water stream, the mountain itself or from the family who owned these lands and its ancient castle. The toponym, as Luigi Michelini Tocci (one of the most productive local historians ever) says, actually comes from “cardo” (thistle), one of the most common plants in the surroundings, while “the Carda” is the name of the area enclosed between the two easily recognizable mountain ridges. The highest one belongs to Mount Cardamagna and tops over 900 meters, representing almost a defensive stronghold for Mount Nerone, while the other one (called “La Cardaccia”) is 200 meters lower and was once hosting the Castle. In front of the ridges, across the road connecting Piobbico and Pianello with Pian di Trebbio, the Carda is clearly delimited by the mounts of Serra della Stretta, which holds the little village of Acquapartita on the opposite side.

The Castle of Carda was located right above Fosso del Mulino and San Cristoforo di Carda, but unfortunately today we just have a few ruins left, scattered on the mountain slope. It belonged to the Brancaleoni, the most powerful Piobbico family, since the XII century (even if most probably it was built much earlier), later became property of the Bishop of Città di Castello and at the end of the XIII century it was given as a gift to the famous Cardinal Ottaviano Degli Ubaldini, damned in the Epicureans circle in Dante’s Inferno together with Emperor Frederick II, whom he apparently supported. Ottaviano was in fact considered heretical because his family belonged to the Ghibelline party and this was sufficient at the time to deserve burning in Hell’s fire for eternity, even if the facts would demonstrate that he was actually leading the Guelph army from Bologna against the Emperor and that the Pope himself appointed him to conquer back the Church lands in the Po river valley. In any case Ottaviano was probably the first famous member of the family that was to become in control of the Apecchio area, the Ubaldini, coming originally from Mugello in Tuscany and then, through continuous wars and alliances, reaching the present Province of Pesaro and Urbino. Ottaviano gave the castle to his grandnephew Tano, who became the ancestor of the local branch of the family, the Ubaldini della Carda.

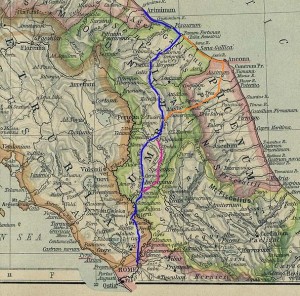

From the Carda the family spread out conquering other castles in the area, and Montevicino, Apecchio, Pietragialla and Castelguelfo fell soon under their Dominion. But the move that most of all sanctioned their fortune was to become allied and “war partners” with the powerful Montefeltro family, providing the Dukes of Urbino with troops and military knowledge in many conflicts throughout Italy. The Ubaldini family was in fact renown for being a forge of commanders and among its military masters one of the most famous representatives was Giovanni Ubaldini, who was capable in the XIII century to found his own “company of fortune”, with over a thousand soldiers and two thousand horsemen coming from all over Europe.

Bernardino degli Ubaldini was born at the end of XIV century, probably in the Carda, and he was maybe one of the most celebrated captains of his age, gaining the nickname of Magnifico (The Magnificent). His pronounced abilities as a war leader made him become very close to the Duke of Urbino, Guidantonio, who wanted him as a partner, and his value and strategic importance grew bigger with time until he was honoured with becoming a family member by marrying Guidantonio’s daughter Aura in 1420.

Bernardino definitely had a natural son, called Ottaviano like his forefather, but according to what in the past seemed to be nothing more than a rumor that later revealed itself as more than truthful, he was as well the father of Federico, the most acclaimed among all Dukes of Montefeltro. Until not long ago it seemed certain that Federico was born from an affair Guidubaldo had with one of the court’s ladies, and for this reason he was considered illegitimate. He was then given in custody very soon to a family in Mercatello, and later at the age of eleven he was sent to Venice apparently not only as a pledge of peace according to the customs of the time, but also to accommodate the will of Guidantonio’s second wife, who was not very happy to have him around in Urbino.

Several studies were carried on regarding Federico and his birth, but the recent publications (1) from the Apecchio historians Lionello Bei and Stefano Cristini are worth mentioning, as well as the articles by the same authors published on the VERSACRUM local history blog. As it also appears from their researches the argument is today much more debated comparing to the seemingly solid truth of the past, and we can even come to the conclusion that Federico was indeed son of Bernardino Ubaldini Della Carda, and that his natural father was so much committed to Guidantonio (who was not succeeding in having a male successor and therefore in granting stability to the State) to give away his first born son, making him at all effects a Montefeltro.

Ottaviano Ubaldini Della Carda was born in 1424, two years after his brother, and followed his fate, being sent very soon away from home to the Visconti Dukes of Milan again as a pledge for the peace reached between the two families.

As noted by Michelini Tocci the two boys, either they were brothers or not and despite the long periods of time they were apart, became great friends as their “official” fathers also were, and remained attached to each other for the rest of their lives.

In 1437 Bernardino Della Carda died, leaving as legitimate heir of all his possessions Ottaviano, but he decided also to split equally his army between Ottaviano and Federico, proving his strong tie towards both of the two young men. But Ottaviano was more keen on books, leading the troops into battle was too big of a burden to him and so he decided to leave the complete command to Federico, who found himself very young in charge of eight hundred spears.

Federico was a natural born leader, with exceptional strength and endurance and by heading his army at the service of the highest bidder he gained more and more public exposure thanks to his continuous victories. In 1441 took place maybe his most intrepid action ever, when he was able to take San Leo from the Malatesta family, climbing with a handful of men the steep cliff, taking the fortress and becoming in this way a celebrity all over Italy.

Despite his success he could not though claim to himself the Dukedom of Urbino, since in the meantime was born the legitimate son of Guidantonio, Oddantonio, who became Duke when his father died in 1443.

Everything seemed to fall into place following the most logical scheme of things, with Urbino having granted the blood succession and consequently its political stability and with Federico continuing the life he loved most as a soldier. But not even one year after being invested, Oddantonio was assassinated after the famous conspiracy plotted by his closest counsellors, shuffling cards once again. Federico was fighting in Pesaro when he was urgently summoned back home and declared Duke by the overwhelming pressure of the people, despite the insisting rumours (even though coming mostly from the rivals Malatesta) pointing at him as the mastermind behind the plot.

Starting from his investiture as the new Duke, Urbino will have his best period in all history, thanks not only to his military skills but also (and maybe above all) to the political and administrative abilities of his “brother”, who had been almost forgotten in his exile in Milan.

Ottaviano was a very smart guy, serious and with uncommon good sense, self control and stern and almost mystical severity, and within a few years he had been able to become (although he was still considered as a hostage) very dear to the Duke Filippo Maria Visconti and to represent an important figure in the court of Milan, as the time chronicles tell us.

Great academic, he was able to have access to huge libraries and to have some of the most eminent and erudite men of his time as teachers. In those days among all sciences astrology was having a very important role especially within the palaces. It seems like the Duke of Milan did not want to move a finger without consulting with his astrologers first and as a consequence Ottaviano himself was hit by a quite deep and specific “magic” education.

Ottaviano remained in Milan until the death of Duke Visconti, in 1447, then he returned to his beloved and never forgotten Carda, and to Urbino, where Federico called him to share the government of the State. Thirty five years of cooperation with the Duke will follow, forming in fact a diarchy that was one of the most enlightened and efficient government systems of the time. Federico took care of the war matters and contributed to the biggest part of the Urbino income with his military services sold all over Italy, while Ottaviano was the real ruler and his accurate and forward-thinking management made the ducal city one of the most important centers for the Humanistic culture and the Renaissance arts, creating also a true political reference point for all Europe. Ottaviano, together also with Federico, continued to be involved with astrology and the importance of this science was so big at the court of Urbino that after the building of the Ducal Palace (Palazzo Ducale) the front towers (Torricini) became observatories and home to the many other astrologers called in the city to share their knowledge. This is to many the best time for the Duchy, enriched by the presence of Laurana and Francesco di Giorgio Martini, with the latter depicting the engine of the enthusiasm impregnating the whole State in the famous marble lunette showing Federico close to a military sign and Ottaviano with two books and an olive twig.

The two rulers did not forget about their origins and the Carda. Federico built a hunting residence in the village of Colombara, and one of the buildings still present today near S.Cristoforo is attributed to the great architect Francesco di Giorgio.

The enchanted period came to an end with the death of the Duke in 1482, during one of his countless military campaigns.

Ottaviano continued to administer the State even after the power went to Federico’s son, Guidubaldo, arranging his wedding with the pupil of another powerful Italian family, Elisabetta Gonzaga. At this point of time his meticulous work as an alchemist and astrologer pushed him a bit too far with the interpretation of the heavenly signs, since he asked the two newlyweds to wait for the most favourable time before consummating their union. Unfortunately the stars alignment was not propitious and the right time never arrived. As the days passed the information leaked out and spread into the city, making the wait of the court the one of the entire Duchy and adding even more pressure on the two spouses. Guidubaldo particularly suffered from neurosis that got worse and worse during that time, and resulted in a deep crisis that did not allow the marriage to be ever consummated, making him by fact the last member of the Montefeltro dynasty.

The Sorcerer of the Carda was accused of witchcraft and of “putting up the show” just to keep the power for himself, making the last decade of his life a dark period, not worthy of his absolute greatness as a statesman, but despite all he continued to hold the reins of the government of the Duchy until his death in 1498.

He was laid to rest in the church of St. Francis in Cagli, where anyhow his burial place was never clearly identified, as if even after being dead he had to remain in the shade as he had done throughout his life.

But the Sorcerer of the Carda was so bound to his homeland that it seems almost impossible he did not want to remain close to it through eternity, and in fact rumors continue to spread whispering he is still roaming around the ruins of the Cardaccia and in the Gamberaia Gorge and maybe even today, when wandering on the trails of the western side of Mount Nerone, someone can still feel his presence.

Based on “Storia di un mago e di cento castelli” by Luigi Michelini Tocci

Lucio Magi © 2016

(1)

“La doppia anima. La vera storia di Ottaviano Ubaldini e Federico da Montefeltro” Bei-Cristini

“Vita e gesta del magnifico Bernardino Ubaldini della Carda” Bei-Cristini

http://versacrumricerche.blogspot.it/p/la-vera-paternita-di-federico-da.html

http://versacrumricerche.blogspot.it/p/via-e-gesta-del-magnifico-bernardino.html

(2)

Image from Wikimedia Commons