| CAI Pesaro | |

| CAI Montefeltro | |

| CAI Rimini | |

|

CAI Ancona |

|

CAI Fabriano |

|

Lupus in Fabula |

|

Camminando Monti e Valli |

|

La Cordata |

| Il Ponticello |

Category: Trek

Indra Treks 2016

The official Treks Schedule for January-June 2016 is ready and can be reviewed here.

More details will follow in the next weeks (itinerary, difficulty, lenght, etc.)

To make easier the interaction with whoever would like to join our treks we have opened a Facebook webpage that will be the official channel for all “quick” communications, leaving any other detail to this web site.

The opening will be on January 31st 2016 with a new trail at Alpe della Luna.

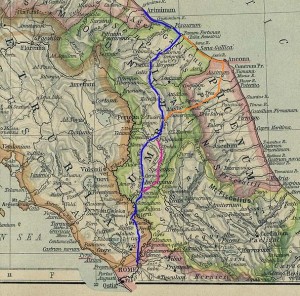

The Byzantine Corridor

Travelling in the Byzantine Corridor, the idea for a Trail

Wandering around some of the most hidden corners in the Province of Pesaro-Urbino on the border with Umbria you may very likely happen to enter, without even knowing most of the times, a territory that starting from the second half of the VI century AD and until the end of the Lombards dominion was the only passage capable to connect the two main power centers in Italy within the relics of the dismembered Western Roman Empire.

We are talking about the Byzantine Corridor, a land strip running through Marche, Umbria and Lazio and linking Ravenna with Rome. The ancient Flaminia Road, preferred way of communication in the earlier centuries, was now interrupted since the narrow Furlo Pass, gateway along the artery connecting Rimini with the old Imperial Capitol, was now under the Lombards control. It was hence absolutely fundamental to find an alternative route to connect the Exarchate in Ravenna and the Pentapolis (a city union including Rimini, Pesaro, Fano, Senigallia and Ancona) with Rome and for this reason the Corridor was passing through many impervious regions, mostly in the mountains and therefore well defendable, where the Lombards could not yet reach.

The Byzantine Corridor

The Lombards invaded Italy in 568 AD, after the war against the Goths to regain the territories once belonging to the Western Roman Empire had exhausted the Byzantines. For this reason and due to the fact that the best troops were called back to Byzantium and to Asia to fight against the Avars and the Persians, the submission of a good part of the Peninsula was quite easy for the Lombards.

The Byzantines were able to keep under their dominion a few areas among which were the Exarchate and the Pentapolis, as well as the majority of Lazio and Southern Italy, but the Lombards were indeed extending their influence to the Center and the South with the Duchies of Spoleto and Benevento, and the Continental Italy was in fact broken in two separate areas with no connection in between, except for the Byzantine Corridor.

In such a borderland like the Corridor was, as one can imagine, was living a variety of peoples and cultures either of local origin or foreigners arrived with the barbarian ords, all with their traditions and, above all, with their Gods and Patron Saints.

Christianity had already spread everywhere, after being equalized to the other religions by Costantino and especially after becoming the only Empire official religion with Teodosio in 380 AD, but in the remoteness of the Corridor many still followed Paganism, as shown by plenty of examples of churches built in this area on top of Altars originally erected to venerate Jupiter or Apollo.

The Lombards were originally worshipping (as many other peoples coming from the North) Ases like Thor and Odin, and they approached Catholicism just for convenience way before their descent in Italy, when they had to ingratiate precisely the Byzantines, their allies during the stay in Pannonia (current Hungary).

The decision to invade the Peninsula changed things around, and the Lombard king Alboino commanded, in order to irritate the Byzantines, to join in stead one of the Heresies officially condemned by the Council of Nicea, Arianism, which had dared to deny the Trinity and put Christ on a lower level compared to the Father, and which was by cohincidence also the Religion of his main potential allies against Ravenna, the Goths, who were still present in the territory despite their previous defeat.

Once in Italy the Lombards merged more and more with the local population, and eventually massively converted to Catholicism. During this process of conversion they ended up adopting as Patron Saints the ones that maybe resembled more their ancient Gods and among them one of the most important was certainly Saint Michael Archangel, who had abandoned Satan in the Christian tradition and defended the True Faith with his sword, in whom the Lombards were recognizing most probably the God Odin.

Even the Byzantines, the Lombards’ rivals, had their own Patron Saints and were particularly devoted to Saint Martin of Tours, protector of the Catholic faith from all heresies, and especially from Arianism, against which he had personally fought. To prove the importance of this Saint the current Basilica of St. Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, raised as Arian Church when the Goths conquered the city, was dedicated indeed to Saint Martin after the Byzantines took it back.

Based on this historical premise, the authors of a recent research made in cooperation with the University of Urbino demonstrate that it is possible to locate the borders of the Byzantine Corridor analysing the toponyms of the sites and of the religious buildings present on the territory. As an example many are the cases of churches consacrated and sites referenced to St. Michael Archangel to testify the Lombard dominion, as well as clearly all the ones dedicated to St. Martin must be linked to the Byzantines. In some cases we even have two rival Saints facing each other in churches built on the opposite sides of a valley or a river, just like they were the real generals leading the two opposing armies.

St. Michael Archangel painted by Guido Reni

From the results of this work we can then try to sketch a travelling itinerary that, following the tracks identified by the historians, takes us to discover a portion of the Byzantine Corridor in the Province of Pesaro-Urbino and that jumping from Byzantine to Lombard possessions leads us from the border with Umbria, following the main rivers, to the Furlo Gorge and then to reach the Adriatic Sea.

The territory where we will travel is mostly mountaineous and bumpy, close to the North West limit of two mountain ranges running parallel to the coast, the Umbrian-Marquesan range and the proper Marquesan one. The first developes on the border bewteeen the two regions and includes Mount Catria, Nerone and Petrano, while the mountains forming the Furlo Gorge (Pietralata and Paganuccio) belong to the Marquesan range.

The main rivers in the area flow perpendicularly to the ranges, creating at times narrow canyons and at times wider valleys. The Burano river, the first we will meet along our trail, starts in Umbria and from here, after crossing the first of the two ranges, arrives in the city of Cagli. Continuing its flowing to the sea it becomes tributary of another river, the Candigliano, also coming from Umbria, which after cutting like a razor the anticline of the second range and creating the Furlo Gorge, drops into the more famous Metauro river.

The Flaminia Road

Let’s start then from Pontericcioli, right on the Burano river on the border of the Province, that was once an ancient Umbrian city later conquered by the Romans and that became with time an important center along the Flaminia Road. Pontericcioli can be reached from Fano via the freeway to Fossombrone and Cagli, or from Gubbio and Scheggia if you are travelling on the old Flaminia Road from Rome. Nowadays it is a small town famous for its Roman bridge Ponte Grosso and for its possible identification with the Roman municipality of Luceoli dated I century BC. Here already we can see by studying the toponymy that the high Burano valley was under the control of Ravenna, and we can tell just because we have references to another important figure connected to the Byzantines, St. Apollinare, who is said being direct disciple of Saint Peter and first Bishop of Ravenna.

Over Mount Petria, just in front of the more renowed Catria and dividing Pontericcioli from the community of Chiaserna, things were quite different. Here in fact both the church of St. Anastasia right in the village centre (Anastasia can be connected to the typical Gothic ritual of the Resurrection or Anastasis) and the Abbey of St. Angelo, in the surroundings of Chiaserna along the Bevano stream, speak very clearly in saying that the valley was populated by people of Barbarian origin.

Continuing North we reach the little town of Cantiano, right on the crossroads between the “Byzantine way” along the Burano valley and the “Lombard way” from Chiaserna, and from here we continue to the village of Moria, scrambled on the South West side of Mount Petrano, where we find another church dedicated to St. Apollinare. Not too far, between the two small villages of Caimarini and Caimercati, we also have a site still known today as Hill of St. Martin and both the toponyms make us understand that the Corridor was going right through this area. Mount Petrano had been in fact massively fortified by the Byzantines, even if today we have very little remainings of this powerful defensive system protecting the Flaminia Road and Luceoli.

Looking again to the North, on the opposite side of another tributary of the Burano, the Bosso (famous for its canyon and the open-air geological museum), we have another important massif in the area, Mount Nerone, which was strongly guarded by the Lombard troops as demonstrated by the two churches consacrated to St. Michael Archangel in Cerreto and Fosto. The first is a small community reachable from the village of Pianello, while the second is also a small village but on the road connecting Secchiano to Piobbico. Mount Nerone seems to have been much less militarized with towers and castles than Mount Petrano, and this could very well be explained with the simple fact that the Lombards were outnumbering the Byzantines and did not need to control a very narrow crossing among enemy lines as their rivals were forced to do.

But let’s leave again the Lombard zone to continue along our Corridor Trail, which from Moria takes us to the top of Mount Petrano and then, following its gentle profile and crossing its grazings, goes down to the opposite side of the mountain just near Cagli.

This important town was a huge stronghold for the Byzantine defense but is crowded with references to the Lombards. We find again here, besides the “same old” St. Michael Archangel (oddly becoming also part of the town’s emblem after it was rebuilt and re-baptized St. Angel Papal from Pope Niccolò VI at the end of 1200), also mentions to other figures dear to the Lombards, like Saint Savin. The Bosso narrow valley was also interdicted to the Byzantines, as shown by the name of the local Staffolino Bridge (coming from the German word “staffal”, meaning pole), as well as there was no way out from the canyon between Mount Petrano and Tenetra. It looks like Cagli was completely surrounded by the Lombards and it is very difficult here to find a crossing in between enemy lines. But following the by-now-friends toponyms, the historians were able to reveal a passage coming down from Mount Petrano directly on the Flaminia Road just outside town. From here you could wade across the Burano on the right bank and then, further down near the other village of Smirra, cross again on the opposite side bypassing the enemy troops around Cagli.

The way was then continuing to another important stronghold now destroyed but appearing in many proofs, the Castrum (castle) of St. Martin, protecting the way towards Fermignano, another important town in the Metauro Valley. After eluding the Furlo Pass it was finally possible to enter the more secure and far from the border land of Montefeltro, to reach Urbino and then Rimini.

This was not the only safe itinerary for the travellers though. The toponyms studies lead us to think there were other crossings between the Lombard armies and that more branches of the Corridor were used at the same time. Going back to the beginning of our trip for instance, in the valley of Cantiano, there are clear tracks of a passage from Pieve St. Crescentino near Balbano (built back in the beginning of Christianity and famous for its important frescoes) to another important center in the area, Apecchio, eluding the Lombard troops on Mount Nerone.

Further down towards the coast, just after the Furlo Pass, if you wanted to travel to the closest member of the Pentapolis, Fano, you needed to divert to where now are the villages of Calmazzo and Canavaccio, and then continue along the Flaminia Road until Fanum Fortunae. It is quite interesting to note that in the area of Calmazzo we find track of a possible demilitarized zone, identified near St. Bartolomeo di Gaifa (Gaifa comes from the lombard word waifa, meaning “land that does not belong to anyone”), where most probably for common interest or agreement between the two parties there was no fighting taking place.

In times of more and more developement of slow tourism and with the growing of the number of new itineraries, I think that the design of a multi-stage trail along the Byzantine Corridor could be a very stimulating idea to put into practice.

Obviously we are talking about the idea of a quite different itinerary than the ones proposed along the Sacred Ways and born often after the Camino de Santiago “master” concept, but I think this would not make the trip certainly less fascinating.

We are not dealing with a hike on a Pilgrimage way but we are thinking of an itinerary crossing an ancient area where for centuries troops and civilians inevitably walked due to war, leaving proofs, building fortresses and villages, and modifying permanently the local culture and traditions, and in this perspective it could only offer a potential traveller willing to walk it today a countless number of experiences, historical and religious, cultural and artistic, naturalistic and environmental.

Furthermore we should not forget, always thinking about an hypothetical slow trip in this fantastic territory within the Province of Pesaro-Urbino (I know I am biased..) the “enemy lands” occupied by the Lombards, that are not less meaningful compared to the Byzantine ones and deserve certainly interesting detours and follow-ups.

What once was the most dangerous Furlo Pass is now included into a State Natural Reserve, with all its beauty and richness that would alone deserve the trip, while the fearsome Lombard bastions of Mount Nerone are now regularly occupied by trekkers, bikers and climbers.

For the moment being anyhow the Byzantine Corridor Trail remains just an idea and it is possible to travel along the itinerary just following the toponyms and not the signs. We can only try to stimulate the curiosity and the adventurous spirit of people willing to follow the footsteps of a traveller in the VII century AD, trying to reach the Adriatic sea from Rome or viceversa. The main purpose is though to be able to develop the idea in the near future beginning, why not, from publishing new articles with all the stages of this potential Trail narrated in all their details.

For who wants to get deeper (and can read Italian..) with the historical, geographical and toponymy contents in the Byzantine Corridor and in the territory crossed in the Province of Pesaro and Urbino it is mandatory to read the book that inspired this article, and from where I borrowed all the toponymy information. “Il Corridoio Bizantino al confine tra Marche e Umbria” was published in 2014 and is the result of the meticulous and passionate research made by the authors Giuseppe Dromedari, Gabriele Presciutti e Maurizio Presciutti, to whom goes a very special thanks.

Lucio Magi – October 2015